By Cindy Reich

This column appeared in the May 2007 issue of Arabian Horse World.

Our lives are ruled at the moment by mare’s ovaries. It’s that simple. Considerations of follicle size, number, rate of growth, time of ovulation far outweigh mundane things such eating or sleeping. We are glued to the ultrasound screens all morning — measuring follicles, analyzing their shape, size, and consistency. We chart their growth or lack of it, look for patterns in previous heat cycles, and put forth full effort to coordinate breeding with the ovulation of a dominant follicle.

Before the days of ultrasound, breeding was a very hit-or-miss affair. Unlike other types of livestock, mares can ovulate at any time during their cycle. Therefore, it requires some effort to determine what is “normal” for each mare. While one mare might ovulate five days after coming into heat and another might ovulate two days after coming into heat, another mare might ovulate two days after going out of heat. Decisions were made on a “best guess” after the veterinarian had been out to palpate the mare. Palpation was, at best, an inexact science due to the structure of the ovaries of a mare.

The ovaries of a mare are somewhat kidney bean-shaped and range in size from walnuts during the non-breeding season to oranges at the height of the breeding season or even grapefruit size under some conditions. As the days get longer and breeding season begins, there is a release of hormones that cause the growth of follicles within the ovary. The follicle is basically a fluid-filled structure that contains an oocyte. The oocyte is the cell that will be fertilized by the sperm cell when conception occurs.

In the early spring, as the ovaries “ramp up” they produce clusters of small follicles that generally just regress and do not ovulate. As the daylight increases from early spring to spring, the frequency and amount of hormone release intensify and the ovaries start to produce a smaller number of larger follicles that ideally go on to ovulate.

This is why putting mares under lights in December will cause the same hormonal release before the breeding season starts that would normally occur in early spring. The ovaries will go through their transitional period prior to February so that by the start of the breeding season, the mare’s ovaries are responding as they would in the normal daylight of May. With mature follicles developing and ovulating early in the season, the mare has a much better chance of going in foal for those who breed for early foals.

Foaling season is still going strong – at least out here in the West. Although show and race breeders want early foals, most breeders are content to have them born when the weather and the grass are most advantageous for outdoor foaling. With June one of the most fertile months for mares to be bred, there is a second bubble of foals coming right now.

In the last few weeks there have been a number of cases that caused me to write down a few notes on some common problems that can occur throughout the season. Many have been explored in depth in previous columns, so this will be somewhat of an overview.

Neonatal Isoerythrolysis

Right now we have a mare in the foaling stall that is considered a candidate for having a neonatal isoerythrolysis (NI) foal. This condition results when a mare’s immune system has built up antibodies to the foal’s blood type. There are several ways this can occur. It can happen when a foal inherits a blood type from the stallion that is foreign to the mare (there are seven different blood groups in horses). Mares that have had multiple foals might have had some leakage from the placenta that allowed some blood from the foal to enter the mare’s circulatory system and sensitive against the foal. Mares that received blood products early in life may have a sensitized immune system as well.

What happens in an NI foal is that the antibodies the mare has formed against the foal’s blood type concentrate in her colostrum. The function of colostrum is to convey antibodies to the foal to protect it from disease until it develops its own immune system at 5 or 6 months of age. However, not all antibodies are helpful, and in the case of NI foals, the antibodies will seek out and destroy the foal’s red blood cells. Affected foals will become weak and jaundiced (displaying yellow mucous membranes and yellow eye sclera) at around 12-24 hours of age and can die. It is much easier to prevent this condition from happening in the suspected NI foal than to try to treat and save it if it is affected. Since the mare’s colostrum is only produced for approximately 24 hours, the fix is fairly easy. The foal should be muzzled immediately after birth. It should be fed on a bottle for at least 36 hours and the mare’s colostrum should be stripped and discarded. Obviously an alternate source of colostrum needs to be found for the foal because it can utilize the colostrum for the first 24 hours of life. Access to a colostrum bank is ideal, but if no alternate colostrum can be obtained, the foal will have to have plasma administered instead.

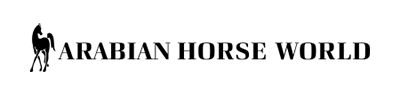

Multiple small follicles

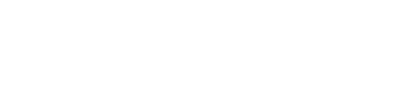

Large dominant follicle

In this column we’ll explore what happens in the mare when follicles develop and ovulate. In June’s column, we’ll look at recent extraordinary developments in reproductive follicular research that is already producing results for owners of old, infertile mares.

What causes a mare to develop follicles?

Lengthening daylight is the stimulus to mares that begins the process. As the length of day increases, the hormone melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland within the brain, decreases. The decrease of melatonin levels allows the release of the hormone GnRH (gonadotropin releasing hormone). The GnRH is released initially in pulses or cycles and the amount of hormone released increases as the pulses increase. This is why during the transitional period of winter/spring, spring/summer, it takes awhile for the system to ramp up. Therefore the mare will often have erratic (often very long) estrous cycles and the ovaries will start producing large numbers of small follicles (10-15-20mm), often referred to as “clumps of grapes.” Usually these follicles simply regress and others start growing. There may be some larger follicles (25- 30mm) but they usually will regress as well. Think of it as “priming the pump” for the production of large, mature, ovulatory follicles.

The rising frequency and amount of GnRH being released acts on the hypothalamus in the brain to cause the release of two more important hormones: FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and LH (luteinizing hormone). Yet another hormone, estrogen, also comes into play, causing the relaxation of the cervix and uterus and contributing to the development of the mature, ovulatory follicle.

The estrous cycle

Early in the estrous cycle, there is a release of FSH that stimulates follicle production. Generally, a few midsize follicles will form. As those follicles grow, one follicle will usually become dominant and will mature in tandem with the release of the LH that has increased as the levels of FSH decrease.

As the dominant follicle matures, the release of estrogen stimulates an increased surge in LH. The estrogen also has an effect on the behavior of the mare as well as causing a relaxation of the cervix and uterus. The dominant follicle will also release a substance known as inhibin that discourages the further development of ovulatory follicles. However, as we all know, mares are fully capable of having multiple ovulations.

What happens at ovulation?

The mare is very different from the cow for example, in that ovulation occurs in the middle of the ovary where there is a small “pit” called the ovulation fossa. In cattle, ovulation occurs at the outer surface of the ovary where the fallopian tube forms a “cap” over the ovary. These are two very different ways of ovulation. However, this difference caused a lot of difficulty in the days before ultrasound, because veterinarians who had to manually palpate mares to try to determine if mares were ready to ovulate had an incomplete picture. Since, in the mare, ovulation occurs to the center of the interior of the ovary, any “bulge” felt on the outside surface could be much bigger than what could be felt. For example, if the veterinarian felt a structure that was 20mm in size, there might have been 30mm of follicle inside the ovary that was not palpable. Therefore, a call of a 20mm follicle as opposed to a 50mm follicle could have very different outcomes. It is amazing that we got mares in foal at all!

However, modern technology aside, the behavior of the mare, the texture of the uterus and cervix and other clues gave added information as to whether this mare was really on the verge of ovulating or not, although it was still a “best guesstimate” way of predicting ovulation.

With the advent of ultrasound, we gained the ability to see the follicle itself and accurately track its progress and ovulation with certainty, thus taking the guesswork out of the procedure.

As the follicle matures, it will often gain 5mm a day in size. Most mares will ovulate when the follicle has reached a size of 45mm or more. Again, however, the only thing consistent about mares is their inconsistency, and each mare must be followed to determine what is “normal” for her. If one is following the mare’s cycle closely via ultrasound, as the follicle gets closer to ovulating the wall of the follicle will become thinner and the follicle will take on a triangular “guitar pick” form as it prepares to rupture into the ovulation fossa.

When the follicle ruptures (ovulates), the oocyte is deposited into the ovulation fossa. The tip of the oviduct is attached to the fossa and the oocyte makes its way down the oviduct to the utero-tubal junction where it will await the arrival of spermatozoa and where, if everything goes according to plan, fertilization will occur.

Corpus hemorrhagicum

After ovulation

After ovulation, the cavity that was once a fluid-filled follicle fills with blood and is called a corpus hemorrhagicum (bloody body). It is sort of like a big hematoma within the ovary. As the blood inside clots, the structure that then forms by 5 days after ovulation is called a corpus luteum (yellow body). The corpus lutem (CL) then begins to secrete progesterone. As progesterone levels rise, estrogen levels decrease, the mare goes out of heat and if fertilization has occurred, the CL will be the primary structure to produce the hormone of pregnancy, progesterone. If fertilization does not occur, about 15 days after forming, the CL will start to break down due to a release of the hormone prostaglandin F2 alpha that is released from the endometrium of the uterus. That is why, in cases where an owner might want to short cycle a mare that has ovulated but perhaps not been bred, an injection of PGF2 alpha given at least 5 days post ovulation will cause the CL to break down and the levels of FSH, LH, and estrogen to rise.

Giving prostaglandin before the CL is fully formed and mature will have no effect. In some cases, mares that did not conceive may have a persistent CL where the CL does not break down and continues to secrete progesterone, keeping the mare from coming into heat and being rebred. Therefore, when doing a post-breeding pregnancy check, it is important to check the ovaries for the presence of a CL as well as a pregnancy.

Hormonal control of estrous cycle

There are many ways to influence or control events surrounding ovulation. The most benign is, of course, the use of artificial lighting schedules to advance the mare’s estrous cycle early in the year.

Progesterone has been used to suppress the estrous cycle in mares. Usually an oral progesterone is given to stop the influence of the hormones that stimulate the development of follicles. The treatment usually lasts for 10-14 days. Once the treatment is stopped and the progesterone level decreases, much like when the CL regresses in a mare’s normal cycle, FSH, LH, and estrogen rise and stimulate a new estrus cycle and follicular development.

Usually prostaglandin is given on the last day of the progesterone treatment to cause the destruction of any CL that might be present in the ovaries.

There are several hormones that have been used to try to accelerate ovulation. Especially with the advent of shipped cooled semen, breeders have been faced with a mare who does not ovulate when expected and cannot get more semen. Therefore, the use of various agents to ensure that ovulation occurs when necessary is not uncommon on many farms.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and Deslorelin are two examples of hormones used to accelerate either the growth of follicles or of ovulation itself.

Anovulatory follicles

Mares can develop a dominant follicle that does not ovulate. Commonly these mares have an unusually long estrous cycle and may be in heat for up to two weeks. Usually these follicles will regress within 4-6 weeks.

Granulosa cell tumor

These theca cell tumors usually affect only one ovary and are both slow growing and benign. A mare with such a tumor may show stallion-like behavior such as teasing, squealing, mounting other mares, and acting aggressively. Affected mares may also show male physical changes if left untreated, such as heavier body muscling, enlarged facial muscling, etc. These mares may have heat cycles, but in at least 25 percent of the cases will show no signs of estrus.

Upon palpation, the ovary will be greatly enlarged, often up to grapefruit size or bigger. I remember one mare we had with a granulosa cell tumor whose ovary was as big as a basketball!

On ultrasound the ovary has a “honeycomb” appearance with thick walled partitions. The mare’s other ovary is usually small and inactive. Usually, once the ovary with the tumor has been removed, the other ovary will become active and the mare’s reproductive life can resume normally. The only difference is that she has one ovary.

Follicles are fascinating in their own way and at this time of the year, I am still seeing them in my sleep as well as spending the days plotting out ways to get them to cooperate with our breeding schedules. But they can be fickle little things as well.

However, thanks to new technology, mares that haven’t produced foals in decades are back in production because although they may have not been able to produce a foal, they were still producing follicles.

Foals, foals everywhere — each one a result of a follicle that contained an oocyte and a sperm cell that penetrated that oocyte. Hard to relate that to the huge foals running circles around their dams in the pastures!