Above: Giulio Rosati (Italian, 1858-1917), Desert Nomads

By Lee S. Dougherty

As featured in the Winter 2024 issue of Arabian Horse World.

What is it about the Bedouin and his horse that has inspired scholars, poets, and artists for so many millennia? Perhaps the finest tributes to the Arabian horse are the Arabic poems composed in its honor, but this ancient breed has captured people’s imagination outside its native land. Sir Edwin Landseer, the foremost animal artist of the Victorian era, painted The Arab Tent (c. 1865-66), a cozy scene depicting an Arabian mare and foal resting within their master’s tent. American author and horse lover Marguerite Henry wrote King of the Wind, a children’s book based on the life of the Godolphin Arabian, one of the three foundation stallions of the modern Thoroughbred. Argentine artist Rúben Bustillo, who passed away in 2022, traveled to Arab lands and painted many detailed images of Arabian horses and their Bedouin masters. His work Life Bond exemplifies the relationship between the horse and the Bedouin and its enduring fascination for so many even today.

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (English, 1802-1873), The Arab Tent.

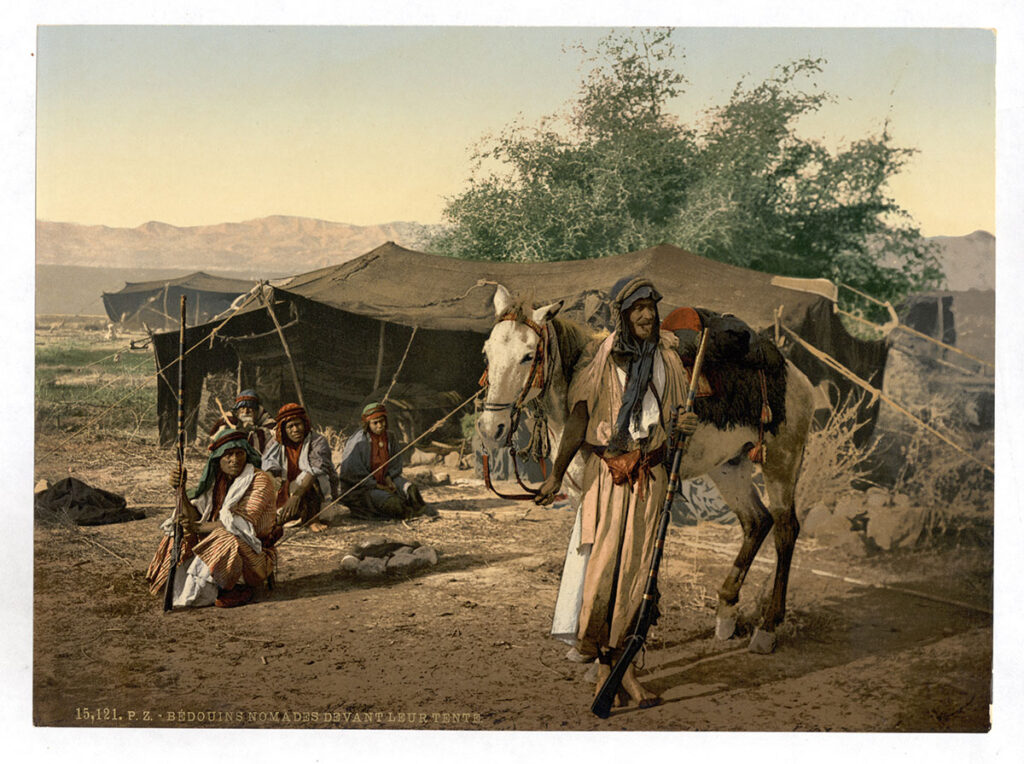

The Bedouins are both Arabs and desert nomads who primarily come from the Arabian Peninsula, the Middle East, and North Africa. The Bedouins consider themselves the true Arabs (a’Rab, “desert dweller”) and also the “heirs of glory.” Their life is not easy, but rather complex and merciless, always hungry and usually thirsty. They usually occupy areas that receive less than 1 1⁄2 inches of rain annually. They frequently relied on pastures nourished by morning dew instead of rain to provide water for their animals.

Most of the Bedouins are animal herders who migrate into the desert during the rainy season. The Bedouin tribes are classified according to the animals from which they get their livelihood. The camel nomads utilize huge territories and are organized into large tribes; the sheep and goat nomads have smaller ranges, and the cattle nomads are found mainly in South Arabia and Sudan. The camel was the Bedouins’ “ship of the desert,” providing them a rugged means of transport as well as milk, meat, and hair for making cloth, but the horse was their treasure. They regarded the horses as Allah’s gift to humanity, to be cherished, loved, and nearly worshiped. They believed that the Arabian’s forehead bulge, the jibbah, held Allah’s blessings. In their oral tradition are many poetic sayings about the horse, such as:

“And Allah took a handful of southerly wind, blew His breath upon it, and created the horse. ‘I have made thee as no other. All the treasures of the earth lie between thine eyes. Thou shalt carry my friends upon thy back. Thy saddle shall be the seat of prayers to me. Thou shalt fly without wings, and conquer without sword, O horse.’”

Unlike the camel, horses are not desert animals, and the inner desert was no place for horses. They would have died there if it were not for the Bedouin’s care—care as good or better as they gave their own children. Before the Bedouin ate his meal, the horse was fed. Even though his offspring might cry for a drink, it is said the Bedouin would pour the last drop of water for his beloved horse. Since grass and water were scarce in the desert, these Arabian horses often ate the same foods as their owners: dates, barley, and camel or goat milk. According to explorer and author Alois Musil, “The more horses a tribe owned, the more feared it was by its neighbors and the greater its power.”

American Colony Photo Department, “Mounted Bedouin Warriors”.

Origins

Though the very beginnings of the Arab horse may be hidden in the ancient desert sands, a vast number of experts agree that the Arabian horse originated in or around the Arabian Peninsula. It is one of the oldest human-developed horse breeds in the world. The proto-Arabian appeared to be a horse with “Oriental” characteristics quite similar to the modern Arabian. Shortly after the horse reached Egypt, 3500 years ago, the artists of that land painted concave-faced horses with high tails on the walls of their pharaohs’ tombs.

Recent archaeological discoveries on the Arabian Peninsula, dating back 9000 years, have uncovered a previously unknown civilization that was based in what is now a desert area. Since 2010, over 300 stone objects, including tools, arrowheads, and animal statues, have been unearthed in the remains of this civilization, called Al-Magar (al-Maqar, “meeting place”). During the Neolithic period, the land was irrigated by a now-lost river, and animals, particularly horses, were first domesticated here. Among the animal art discovered at Al-Magar is a substantial horse statue with a band sculpted across its shoulders and more bands painted across its face. It seems clear that the people of the Al-Magar Civilization used a type of bridle and other tack on their horses. Moreover, some of the horses depicted in other art at Al-Magar show a distinctive short back and concave profile like that of modern Arabian horses.

It’s thought that as the Bedouins moved into central Arabia, they took with them these proto-Arabian horses. Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” idea was in play regarding these horses. The weak were culled, and the strong survived, adapted, and thrived, developing a breed that could survive on little water and almost no pasture: a fast, tough, and robust horse.

The Bedouins depended on their Arabian horse’s incredible speed, stamina, and agility in warfare to capture the enemies’ livestock. Mares were the preferred mounts for raids (ghazu) because, unlike stallions, they do not nicker when they see other horses, enabling the raiders to approach in relative silence.

Among the Bedouins, mares were held in higher esteem than stallions, and certain mares showed great courage in war. Cynthia Culbertson writes, “Bedouin horse breeders emphasized the importance of the mare over the stallion in both warfare and breeding. The love and admiration they felt for their mares, however, is perhaps best expressed through the centuries of Arabic literature. It is here that one can best appreciate not only the physical characteristics the Bedouins prized but also the beauty and spiritual attributes that make the Arabian mare a treasure beyond price.”

Bedouins are generally credited for starting selective horse breeding and originating the Arabian horse. As with their own genealogy, the Bedouins kept pedigree records by memory and transmitted them through oral tradition. They gave horses the epithets Bint (“daughter”) for a filly and Ibn (“son”) for a colt. The Bedouins traced pedigree through the female line. They judged their horses by pedigree and strain; build and performance; color and markings. The Bedouins acquired this knowledge not through textbooks, dogma, or rules but through years of careful observation and the knowledge passed down from their similarly observant ancestors.

The horses with the purest, noblest blood are known as Asil. It was forbidden to permit an Asil to breed with any but another Asil horse. Bedouin tribes also bred and classed other strains (rasan, “rope”) of horses. They believed that the sire’s sire should be the grandsire of the dam. Two fine Arabian stallions, both products of this breeding philosophy, are Jaipur el Perseus and Thettwa Ezzain. In the 1950s, Lloyd C. Brackett applied this approach to breeding German Shepherd dogs, producing more than 90 champions in 12 years. This ancient Bedouin formula is now known as “Brackett’s Formula” in the world of dog breeding. If “Mr. German Shepherd” could pull off such a brilliant success with his dogs, what could this time-honored technique do for the modern horse breeder?

We cannot turn back the hands of time. Bedouin life will not come back from the dead. However, by knowing and understanding the past, we can preserve the valuable heritage left to us from a time characterized by uncertainty and the struggle for survival. Such a heritage transcends the Arabian horse and helps us identify the Bedouin descendants in the modern world. They can be proud of their ancestors’ creation of an incomparable breed of horse whose extraordinary character mirrors the Bedouins’ ancient past values, and whose magnificence continues to captivate artists and authors.